Want concrete strategies for making what you teach more relevant and globally-connected? Enjoy this powerful and extremely useful interview with New York City Humanities teachers, Stephanie N. Ambarsumyan (of Wandering Why Traveler), and Dora DePaolis.

Teaching Traveling: Stephanie, tell us what led to your Global Education travels.

Stephanie: I’m a life-long New Yorker and grew up on Long Island. Immediately after college at 22 years old, I took a teaching job for the New York City public school system and I have been there ever since. In September, I started my eighth year teaching English and Special Education at the high school level.

My school has over 4,000 students and is in Queens — the most diverse borough in New York City. Over 60 different languages are spoken by students and staff at my school. With so many cultures and beliefs represented, my school really is a microcosm of the world.

Working in this environment as an impressionable twenty-something year old solidified my interest in traveling. During spring break of my second year teaching, I booked a trip to Costa Rica with some friends and colleagues, which was my first international trip.

I remember the glowing pride and sheer delight of my Spanish-speaking students when I told them I would be visiting Central America. They were so excited to tell me which foods to try and which phrases to use (all of which I Googled upon returning home after work each day because… teenagers).

When I returned, my students wanted to see every photograph and hear every story. They practically rolled on the floor in laughter (at my expense) and joy when I repeated all of the Spanish I had learned in just one week. A light switch turned “on” and I remember thinking that the act of traveling had enabled me to draw a genuine connection between myself, my students, my classroom, and the world at large. (Metacognition in action: by thinking about my thinking, I can see that travel helps me teach and learn better!)

I was thrilled to share everything I learned with my kids. I think seeing me, their teacher, as someone who could also learn new things and be vulnerable when doing something new, really strengthened our bond. It made me more of a human in their eyes.

As a teacher, you’re kind of expected to know everything. I cannot tell you what a welcome relief it was as a traveler to once again take on the role of a student. I was addicted and quickly became enthralled with learning languages, histories, and reading works of literature from around the world. To this day, when I travel, I take the approach of a perpetual student. I constantly remind myself, I’m not in this country to teach the locals something, I am here as a humble learner. That mentality helps me keep my ears and heart open, I think.

Today it’s several years later and I have traveled to 24 countries — including traveling to Riviera Maya, Mexico to get married in 2018! We have a 15 month old who already has visited Canada, Costa Rica, and countless states in the US.

TT: Amazing! Tell us one moment from your travels that was especially powerful.

S: There was a very particular experience which was a catalyst in my teaching with a more global perspective. I think living in the United States, we’re conditioned to believe that “West is best.” That there is no literature or history more worthwhile of study than that of the United States and the United Kingdom. In the summer of 2015, the blinders fell from my eyes, so to speak.

I was on a trip to Cambodia, infamous for the genocide that took place there in the 1970s. The effects of this devastating event are still entirely evident to this day. I traveled to Phnom Penh, and visited the Cheung Ek Killing Field. That day I experienced the most profound paradigm shift of my sheltered and privileged life.

To start, the fields smelled like death. I mean, I didn’t know that death has an actual smell, but it does, and it lingers at Cheung Ek even decades later. The smell is intolerable and dizzying. It happened to be raining that day, and when this happens at Cheung Ek, the bones of those put into mass graves re-surfaces due to their shallow depth. So, there I stood mere inches from the bones of those killed in the most heinous ways imaginable.

The sensory overload of the fields and the oppressive heat worked in tandem to send me beelining toward the bathroom to splash some water on my face. The restroom was by a fence, and two small children, no older than seven years old, stood at the fence screaming at me and sobbing, begging me for money. I had never seen such abject suffering and poverty in my life. My husband (then boyfriend) had to pry me away from the scene, I was quite literally paralyzed from culture shock.

At the end of the visit, I personally was given the opportunity to speak with a survivor of the genocide who had lost his children and wife in the killings. We could not understand each other very well due to the language barrier, but even in the moments when we were both silently staring at each other, a conversation ensued nonetheless. I could see memories playing like a film in his eyes as he looked at me.

I knew that I had to tell his story. I had to make known the impact of the Khmer people from this tragedy. To make that task a little easier, the man had published a small book about his experience which I purchased from him. Some photos were snapped of the two of us, and I couldn’t maintain my composure. Hot, heavy tears ran down my face as I repeated, “I’m sorry” over and over to this elderly man who only smiled and told me in his best English to please not cry.

How embarrassing it was that this man who had seen so much, now had to comfort this privileged, young woman from the United States. However, I will never forget his parting words. In hesitant English, he told me that I had my whole life ahead of me, and “do good in the world.” So, for the remainder of the trip, I wracked my brain trying to determine how to do that.

TT: What a powerful story! Please continue.

S: In September 2015, following my trip to Cambodia, I was assigned to teach 10th grade English. I wasted no time in gathering resources and materials to teach the novel First They Killed My Father by Loung Ung — a Cambodian genocide survivor. I used the book of the survivor that I met as a supplementary text given its short length. The students were deeply moved by the unit.

We discussed the culture and the history. One student told me that I knew more about the genocide than his own history teacher did. This was my first piece of legitimate proof that travel has significant educational benefits. The students wanted to know more about Cambodia and where else in the world I had been and seen.

Ironically, a few months before March of 2020, a student from one of those 10th grade classes happened to be visiting the high school. He found me, and told me that he saved up money and traveled to Greece after he graduated because he was inspired by my tales of learning through travel. He confirmed that I was engaging in something important. My travels were not frivolous and selfish, but a very vital component to my professional development.

Having seen the success from bringing a global mindset to my English pupils, I worked with my closest friend and colleague Dora DePaolis, to take this way of teaching and develop it into an entire class. Dora is a Social Studies teacher with whom I had collaborated with previously. She is someone who is a terrific resource when I want to offer my students historical background on the works of literature we read. The two of us worked through the summer to develop a Humanities course for senior level students.

My co-teacher is an avid traveler herself with a background in law, political science, and economics. She was even fortunate enough to study abroad in Prague, Czechoslovakia in 1996, just after the fall of Communism.

Our intent for this course was to uplift marginalized voices from around the world and challenge students’ perceptions. Our diverse students were given an opportunity to view history through a completely different lens, by reading literature from people of color from around the world. This opened the door to discussions of US foreign and domestic policy, current events, and the tools authors use their real world experiences to create narratives and poems.

This allowed us to engage in discussion topics for teens that moved far beyond the simplistic “good/bad” dichotomy so prevalent in mainstream US classrooms. Students examined morally ambiguous events and characters, and we asked students to formulate and defend their own ideas on how these issues should be addressed.

TT: Wow! Tell us more about the Humanities curriculum you created.

The course combines teaching history, social science, and global literature. With my literature experience, and her background in US and Global history, we drafted three units for study. The first unit examined contrasted memoirs and the use of analogy in works of fiction. The unit focused primarily on the Middle East, but excerpts from other regions were incorporated into the unit to enable cross-cultural comparisons.

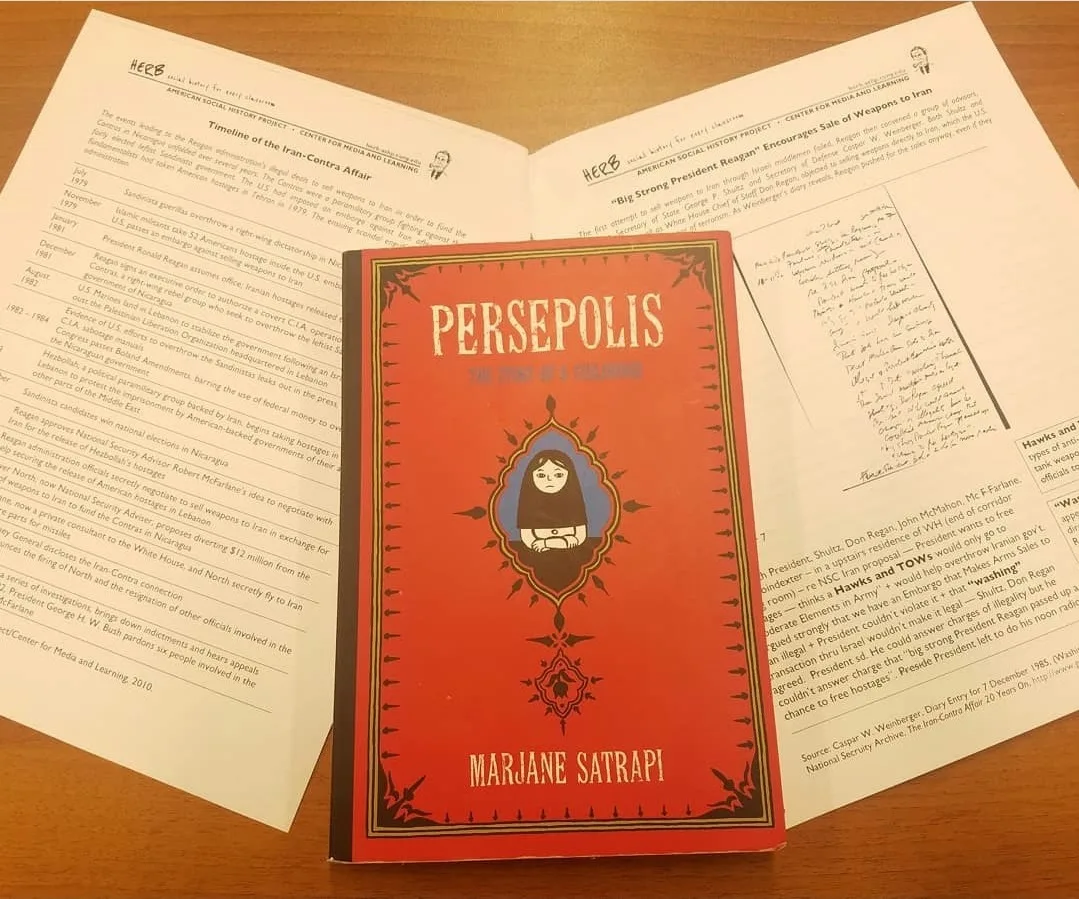

We spent the fall reading Persepolis and The Kite Runner, as well as excerpts from Red Scarf Girl and The Crucible, as well as relevant news articles and poetry. While the unit included included discussions of the historical context and discussions of plot and characterization, we also used the works to discuss issues such as religion as both a toxic and redemptive force; guilt and reconciliation on both a personal and societal level; and the tradeoff between the interests of the state vs. the citizen.

In the winter, we studied African literature and history, focusing primarily on the Congo and Nigeria. Students read Heart of Darkness, Purple Hibiscus, Things Fall Apart, and Black Panther: A Nation Under our Feet, the marvel comic miniseries authored by Ta-Nehsi Coates. The unit began with a discussion of Heart of Darkness as both a work of literature and as a bellwether of cultural norms.

We then contrasted this European take on Africa with works by two renowned Nigerian authors. Purple Hibiscus was particularly fascinating both for its authentic voice, and its connection to the novels we read earlier in the semester, as it is a coming-of-age story that provides insight into historic events that have shaped Nigeria. Our discussions touched on issues such as the short and long term impacts of imperialism; sexism and domestic abuse; the resource curse; as well as map distortion and the tendency for many Westerners to view the continent as a monolithic culture.

We then contrasted the racist or “dark” view of Africa, embodied in Heart of Darkness, with the Black Panther comic authored by Coates, as well as the movie written and directed by Ryan Coogler. Our discussions encompassed topics such as Afrofuturism; the cultural impact of comic books; African vs. African American identity; as well as the controversy over The Help and American Dirt as they relate to systemic racism within the publishing industry, and anti-racist efforts against it. (All ages need to be taught to be anti-racist, starting with educational toys and dolls like these!)

Next year we hope to incorporate a third unit, focused on the Latin American experience, which will incorporate discussions and activities centered around immigration, and the political and social events which have led to thousands of Latinx students to move to the United States each school year.

Another great free resources is these mentor texts by and for teens, which span a wide array of topics and genres and are highly engaging and truly authentic.

TT: Such useful curriculum ideas! Now, what advice do you have for teachers who are dreaming of travel?

S: My advice would be the advice which was given to me by the survivor I met at Cheung Ek. Do good in the world. When you travel abroad, listen with an open heart and mind to the people whose voices aren’t always heard. And when you get home, elevate those stories, because they’re important.

In the case of my trip to Cheung Ek, I knew this man’s story needed to be told. When I returned to work that fall, I found no reason to continue teaching The Great Gatsby when I had this vital story to share with my students. I’m not saying Fitzgerald doesn’t have merit., I would just ask teachers and administrators to really rethink the types of texts and reading experiences we are offering our students, especially in light of the fact that they will be participating in a world that is increasingly interconnected.

Literature can transport our students to anywhere in the world. So, why do we only bring them to the US and England? Seek out authors and stories whose voices are marginalized. This is perhaps the best way to not only teach, but to model social justice.

TT: Thanks so much, Stephanie! Readers, what questions or comments do you have?

The author, Lillie Marshall, is a 6-foot-tall National Board Certified Teacher of English from Boston who has been a public school educator since 2003. She launched TeachingTraveling.com in 2010 to share expert global education resources, and over 1.6 million readers have visited over the past decade. Lillie also runs AroundTheWorld L.com Travel and Life Blog, and DrawingsOf.com for educational art. Do stay in touch via subscribing to her monthly newsletter, and following @WorldLillie on social media!

Amy

Monday 1st of March 2021

I'm happy I have discovered this site. It makes so much sense to incorporate these resources into a curriculum.

Lillie Marshall

Monday 1st of March 2021

I'm so glad you found it! If you have a moment, I'm curious to hear what led you here. Was it a specific web search? Someone suggesting it?